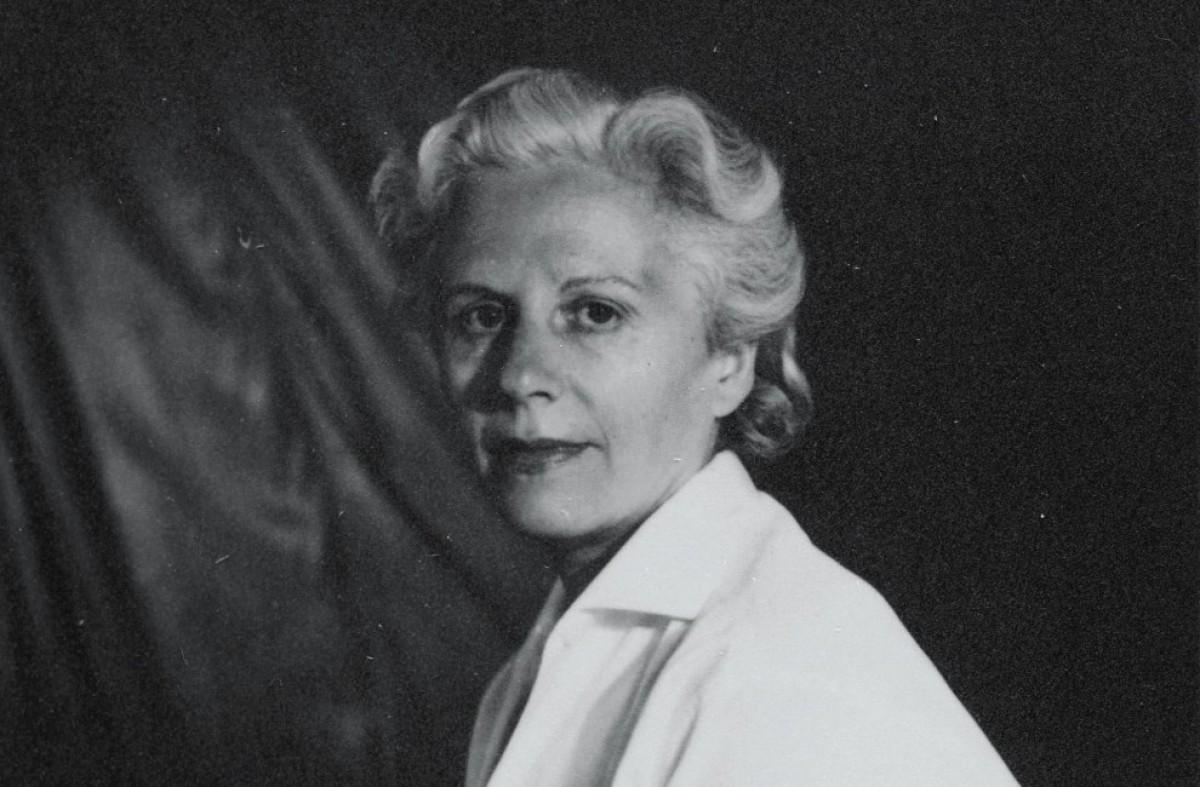

It is no surprise that with every translation published of the work of Mercè Rodoreda (1908–1983), more readers declare to have made a literary discovery. Marcel Proust wrote that the world was not created once, but rather is created again every time a new, original artist emerges: the result looks entirely different from the old world, but perfectly clear. Rodoreda is one of those discoveries that changes the reader’s perspective, because she invites them into a literary world as distinct and sophisticated as Proust’s Paris or William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha. In Rodoreda’s world, there are no decadent aristocrats or bankrupt southerners. There are Catalans disorientated by a twentieth century that has ridden roughshod over them and destroyed their city, Barcelona, which is the epicentre of some of the author’s novels. If Rodoreda is the most important Catalan woman writer of the last century, it is because she transfers a world that only exists in her memory into her books, as often happens in the work of the greatest writers.

Her life is the most crystalline explanation for this ruined world. Rodoreda, daughter of an educated, relatively well-off family, lived through the cultural blossoming of pre-war Barcelona. She worked as a journalist, wrote poetry, plays, stories and novels, and aspired to make a living through writing, making the most of the enormous freedom within her reach. ‘During the Republic,’ the author explained, ‘we all lived an authentic, brilliant, Catalan life. People made contacts straight away, they felt important. And they felt like they were in an important city. Barcelona was, shall we say, an intellectual and progressive hub, a place where things got done. It was an interesting place. And it was a Catalan Barcelona. I don’t know what would have happened to all these writers if things had gone another way’. The Civil War destroyed all her plans and aspirations, as well as those of the rest of her generation’s writers.

Rodoreda was exiled to France in one of the Catalan government’s mobile libraries, leaving her husband from a marriage of convenience and her young son behind in Catalonia. Following a stay in Roissy-en-Brie, a refuge for many writers, she had to flee Paris on foot when the Nazis entered the city. She lived in Limoges, Bordeaux and Paris before finally settling in Geneva, where she stayed from 1954 to 1972. She shared her exile with writer and critic Armand Obiols, with whom she had a tortuous, complicated relationship. Obiols is a central figure in her life and literature, which he followed closely, advising her and guiding her until his death in 1971. And so the most important twentieth-century Catalan woman writer spent the thirty most productive years of her literary career outside of Catalonia. She returned in 1972, moving into a remote house in Romanyà de la Selva, far from Barcelona and the literary scene. Solitude and isolation marked the end of the life of a writer who went to great lengths to describe the ins and outs of the social and cultural scene of her time, transforming it into novels that are based on this world but avoid all costumbrismo because, in her words: ‘I wasn’t born to limit myself to talking about concrete facts’.

The first of Rodoreda’s great female characters is Aloma. This is also the title of the first novel she acknowledged. Isolated in an interior world that overwhelms her and she struggles to understand, Aloma is a teenager who sees how the outside uses and manipulates a desire that she senses but does not yet know or master – a battle fought by many of Rodoreda’s women. She is the first in a dynasty of women who see that there is an enormous distance between what they truly desire and what others expect of them. Aloma is an interior monologue in which Rodoreda practised a skill she would refine and twist throughout her career until her last novel: the ability to delve into her characters’ brains to try to understand the intermittences of their hearts. This exploration of subjectivity is especially brilliant in her short stories, linked with those of authors like Woolf and Mansfield, who Rodoreda read and admired.

The sixties were a golden age for the author’s writing: this was the decade in which she found the financial stability she had been missing since the war, which had led her to live a precarious, survival-orientated life. This was the decade that saw the publication of La plaça del diamant (The Time of the Doves), the novel that placed Rodoreda at the forefront of Catalan literature and that continues to be the most important novel about the Civil War in Catalonia and its consequences, alongside Incerta Glòria (Uncertain Glory) by Joan Sales. The novel’s protagonist is a girl who has had everything taken away from her, even her name. She is a woman consumed by the pressures of an environment that suffocates her until driving her to attempt suicide. It is a raw, merciless novel that examines the destruction of war and its effect on an individual, a city and a country. Having read the manuscript, Obiols wrote: ‘I had a lump in my throat three or four times. The truth on some of its pages sends shivers down the spine. There’s a perfect balance between drama, poetry and banality, which I’m sure very few have achieved. And I’m not saying this after reading a detective novel; I have just finished Demons by Dostoevsky’.

After Colometa in La plaça, Rodoreda intensified the world she had been building to create Cecília Ce, the main character in El carrer de les camèlies (Camellia Street), one of the best novels ever written about Barcelona. The T. S. Eliot quote that introduces the book is no coincidence: ‘I have walked many years in this city’. This quote ties the protagonist to her walks around Barcelona, which tell of her desire to escape her surroundings and herself. Cecília Ce is an abandoned child. As a young girl, she leaves home and wanders the city aimlessly, ‘slightly pathetic, slightly desolate’, like a Baudelairian flanêur. Cecília always lives on the margins, whether in the squalor of the shacks of El Somorrostro or working as a prostitute in a flat in L’Eixample. Rodoreda wrote this novel in Geneva, remembering a city that was no longer her own: ‘The first time I went back after the war, in 1948,’ she writes, ‘Barcelona seemed depressing, sinister. People walked the streets looking sad and despondent’. El carrer de les camèlies is a destructive novel, in which we sense a dark, oneiric world that grows with every subsequent book published by Rodoreda. The writer remembered her city before the war, the image of splendour and the joy that filled the air on the streets. The violent contrast enabled her to describe, from exile, a Barcelona she did not recognise as her own.

A year later, she published Jardí vora el mar (Garden by the Sea), a novel in which she tried out two themes that would come into their own in Mirall trencat (A Broken Mirror): the ravages of time on love and the decline of a family dynasty. In this novel, Rodoreda called upon a type of character she often liked to toy with: rich people devoted to materialistic concerns (like Fitzgerald’s characters) who are as wealthy as they are vacuous. In the book, a gardener tells the story of a couple who spend the summer at a house by the sea for six years, according to what he’s seen and heard. It is a novel, made up of insinuations, that consolidated Rodoreda’s style, full of secret things that can be sensed but are never entirely explained, that prepare the reader to build in their brain everything they sense in the story. Jardí vora el mar starts out abounding with hope and ends in tragedy: a structure that is repeated in a more rounded way in her penultimate finished novel: Mirall trencat.

This novel is the story of a house and the family that lives in it. Rodoreda relates the rise and fall of a dynasty, which echoes the rise and fall of a city, a society and a country. Rodoreda liked books with complex family stories, like William Faulkner’s Sartoris series, which narrates the lives of girls who grow like wildflowers in the colonial mansions of the southern United States. But, rather than a southern cotton plantation, she sets her tale in a detached house in Sant Gervasi. Her intention, though, is the same as Faulkner’s: to recount the decline of a family through the place where they live. The whole spectrum of femininity Rodoreda aimed to portray in her books is represented by the three protagonists in Mirall trencat: one woman is magnetic and good-natured; another is repressed and cold-hearted; and the last is vital and idealistic, and ends up unable to bear the weight life piles on her shoulders. It is the maximum expression of the writer’s realist period, written through the pieces of this mirror that, together, form a fragmented choral voice.

With her last two novels, Quanta, quanta guerra (War, So Much War) and La mort i la primavera (Death in Spring) – the latter left unfinished – Rodoreda explored a world she had played with throughout her literary career. In the former, Rodoreda wanted, in her own words, ‘a novel with little war but with a continuous background of war’. She achieved this through an anti-hero: a teenager who runs away from home, driven by his desire for freedom, which only takes him to a different prison. This is a book about war, fear, love and nihilism; a book that fully belongs to the European tradition of novels about how war changes reality and language. And so does La mort i la primavera – published in English in 2018 as Death in Spring by Penguin – which begins with a meaningful quote: ‘the mystery of this weight I carry inside, that won’t let me breathe’. This is exactly what the reader feels when they read it, when they notice that the book is written by someone trying to breathe while being suffocated. La mort i la primavera is the strangest, most monstrous face of Rodoreda’s world. The story takes place in an unspecific village at an unknown time, where the inhabitants live under an oppressive system that turns them into the living dead. They are men who, despite fearing the darkness, prefer the night to the day, because ‘you could see things too clearly in the light, and the utter hopeless ugliness of some things became too enormous’. The system’s aim is to spread fear and eliminate desire: a desire present in all of Rodoreda’s writing that struggles to emerge into a world that does not accept it.

Armand Obiols wrote that what most impressed him about La plaça del diamant was ‘this kind of interior void, a kind of awe-inspiring pit, [...] it is the final void of all human life, like the void inside a jug, a kind of metaphysical void, which is the nothingness behind all sensations, passions and feelings’. In La mort i la primavera, this void becomes even more present; rather than just implying it, Rodoreda makes it a central theme. This book represents revenge against silence and fear. The novel teaches us that when everyone stays quiet, fear spreads; this is precisely what happens among the village residents, who live under a constant threat they are not even sure really exists. ‘If you live with the belief that the river will carry away the village, you won't think about anything else’, declares one character.

Rodoreda said that the people of her era were surrounded by an intense circulation of blood and death, which are at the core of this novel and paralyse and consume all the villagers’ brains. It is difficult not to think that Rodoreda wrote this dreadful, distressing book to try to shine a light on all the blood and death concealed by fear. Rodoreda understood – as one of her characters says – that ‘there were no words, they had to be made’. And the writer dedicated her life to creating these words, to building a literary world from scratch that was intended to portray her real, disappeared world. ‘A novel is also a magic trick,’ she wrote, ‘it reflects what the author is carrying inside without really knowing that such a burden is weighing them down’. As the years went by, Rodoreda learned to live with this burden on her shoulders: the burden of seeing her country turned into a stifling place. The author suffered under this dead weight, and she found that the only way to lighten it was to avenge all the blood and death with new words.

She once said, ‘Writing is all about finding the right form of expression, the right style’. Rodoreda found it and committed herself to it with ambition, talent and plenty of effort. This writer was entirely devoted to her work – as she admits herself in her correspondence – and managed to elevate it to create a collection of novels the like of which had not yet been seen in her country. ‘In Catalonia,’ she explained, ‘the novel pretends; it doesn’t mean. Or a bit more specifically: it pretends a lot and means little’. It seems that the author, who knew her tradition inside out and could link it to the universal tradition, wanted her work to give meaning to her world again. And she did so with a language that, like that of all original artists, created the world again, making it entirely different from the old one, but perfectly clear. Proust wrote that ‘when nothing subsists of an old past, after the death of people, after the destruction of things’, we need some element that gives birth to the ‘immense edifice of memory’. Rodoreda did this with her memory: she recreated it in her books, and with every new generation of readers who discover it, it will be reborn.

MARINA PORRAS

@mporrasmarti