His name being mentioned in the first decade of the twenty-first century as a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature is testament to his status as a writer who was more distorted than understood. This is all the more evident in light of the fact that, though he enjoyed institutional recognition, he had almost no academic acknowledgement or international influence. His rural origins, self-taught education and roots in a borderland region – with all the complexity that entails – have helped paint a picture of a regional author when, actually, his distilled, sometimes cryptic work reaches a universal dimension. Cerdà sits on the periphery. But this periphery is not just geographical, as an author from Northern Catalonia, struggling against the eclipsing centrality of Catalonia. It is also creative; his oeuvre displays modernity that has nothing to do with the regionalist canons that reigned when he began to write, in the middle of the twentieth century. A relatively brief oeuvre caught between French and Catalan culture, both of which it transcends.

Antoni Cayrol – his real name – was born in the small village of Sallagosa, in Alta Cerdanya, an area filled with livestock farmers in the French state, on 4 November 1920. Before leaving for Perpignan, in 1960, Cayrol worked in his father’s butcher’s shop: a place that became like a school for the poet, who used real things – the most vulgar, everyday realities – as a starting point for his poetry. ‘I had to find the essence of poetry in just a few words’, he explained in an interview conducted by the poet Jean-Baptiste Para for France Culture, in 2001. As a Catalan from the northern side of the ‘line’ – the France-Spain border – and due to the rift caused by Francoism, which cut off all relations between the people of Cerdanya on either side of the frontier, for Cayrol, access to Catalan culture and poetry was a real ‘conquest’. That is why he had to delve into the orality of his language and create from the spoken word. The butcher’s, where he could chat with women from the surrounding villages, thus became the unlikely epicentre of a luxuriant linguistic exchange that allowed the poet to take stock of the ‘life of the language'. At the same time, spurred on by his great intellectual curiosity, he read everything he could get his hands on, accumulating vast, international knowledge.

During the Second World War, in line with his left-wing ideals (an ideological orientation partly inherited from his family), he played a part in the Resistance as a smuggler. His filière let through 350 people – people travelling from or to Algiers – and clandestine letters. ‘We lived in fear of being caught by the police and not being able to keep our silence’, he mentioned in the same interview. Cayrol ended up being awarded the Croix de Guerre with a silver star by the French government. The Occupation was a formative time for him and left an indelible mark on his work. In the play El dia neix per a tothom (The Day is Born for Everyone), for example, he evokes Spanish refugees’ situation during the German occupation through the character of the cattle farmer Peret, a Catalan refugee, traumatised by the Civil War, and his children, who get involved in the Resistance. His political engagement continued with his membership of the French Communist Party, until 2002. This belief in social emancipation flowed through all of his work. It should also be seen as a result of his desire to flee from the restraints of identity and culture, and the weight of traditions and religion.

Cerdanya is Jordi-Pere Cerdà’s literary world. This region, observed through a realistic prism and captured by language coined in the poet’s imagination, is the stage for all his work, whether poetry, plays or prose fiction. ‘Here, Cerdanya is presented as a crossroads between Vic/Ripoll and Lyon, between periods, social strata, cultures, national politics, etc.’, explains Marie Grau, a researcher and expert in the poet’s work. In this sense, one of his most surprising titles is Passos estrets per terres altes (Narrow Paths through High Lands, Columna, 1998), his only novel. Through one female character, Teresa, the writer portrays life in nineteenth-century Cerdanya with prose that, though not a nouveau roman, plunges the reader into a world that can be hard to interpret without knowledge of some key elements.

A more unclassifiable piece is Cant alt, autobiografia literària (High Chant, Literary Autobiography, 1988), in which the writer reflects upon political and social issues and relations with Barcelona and Catalonia. Meanwhile, nature is omnipresent in his work, but rather than being used as a decorative element that serves to create beautiful descriptions, it is an organic whole into which the poet dissolves. Cerdà himself confessed that, through writing, he aspired to ‘brush all that is alive with my fingertips’. As for theatre, his most performed play, out of around fifteen different creations, is Quatre dones i el sol (Four Women and the Sun, 1964) a piece that stands out for the exemplifying dimension of its characters and the repercussions on the study of traditional, patriarchal society, which becomes tougher in wartime.

From the 1960s onwards, Jordi-Pere Cerdà became involved in defending the Catalan language in Northern Catalonia, participating in the creation of the GREC (Rosselló Catalan Studies Group) and the Catalan Summer University. He also carried out some ethnographic work. He published a collection of popular songs titled Contalles de Cerdanya (Stories of Cerdanya, 1959), and in 2016 the posthumous book Cants populars de la Cerdanya i el Rosselló (Popular Songs of Cerdanya and Rosselló) was published. Nonetheless, he maintained a critical stance towards militant Catalan nationalists: ‘Whether they were from the north or the south, he was against those who supported the politicisation of the Catalan issue following a model he deemed valid in the post-Francoist Catalan context, but counterproductive in Northern Catalonia’, Grau points out. It is important to remember that, in French schools, children were taught to be good ‘citoyens’ with slogans like ‘oyez propres, parlez français’ (‘Be clean, speak French’), written on the wall in a school in Aiguatèbia, Conflent. Unlike Catalonia, where Catalan was banned by the Francoist regime, France had a strategy that proved more effective: looking down on any languages (still called ‘regional’, even today) that were not French. In any event, Cerdà’s creative inspiration overflowed from his territory and became part of a humanist emancipation project, with writing as the preferred tool for thought.

Despite this isolation, Jordi-Pere Cerdà is one of the few authors from Northern Catalonia who has managed to publish most of his work in Barcelona, supported especially by Josep Maria de Casacuberta and, in the 1980s, by the poet Àlex Susanna. In fact, he is the only Northern Catalan author to have received the Honorary Prize of Catalan Letters (1995). He had previously been awarded the Crítica Serra d’Or Prize for fiction with Col·locació de personatges en un jardí tancat (Placing Characters in an Enclosed Garden, 1985), the Government of Catalonia’s Saint George’s Cross (1986) and Literature Prize for Poesia completa (Complete Poetry, 1989), the National Literature Prize for Passos estrets per terres altes (1999) and the 2007 Rosselló Mediterranean Prize for Voies étroites sur les hautes terres, the French translation of his novel.

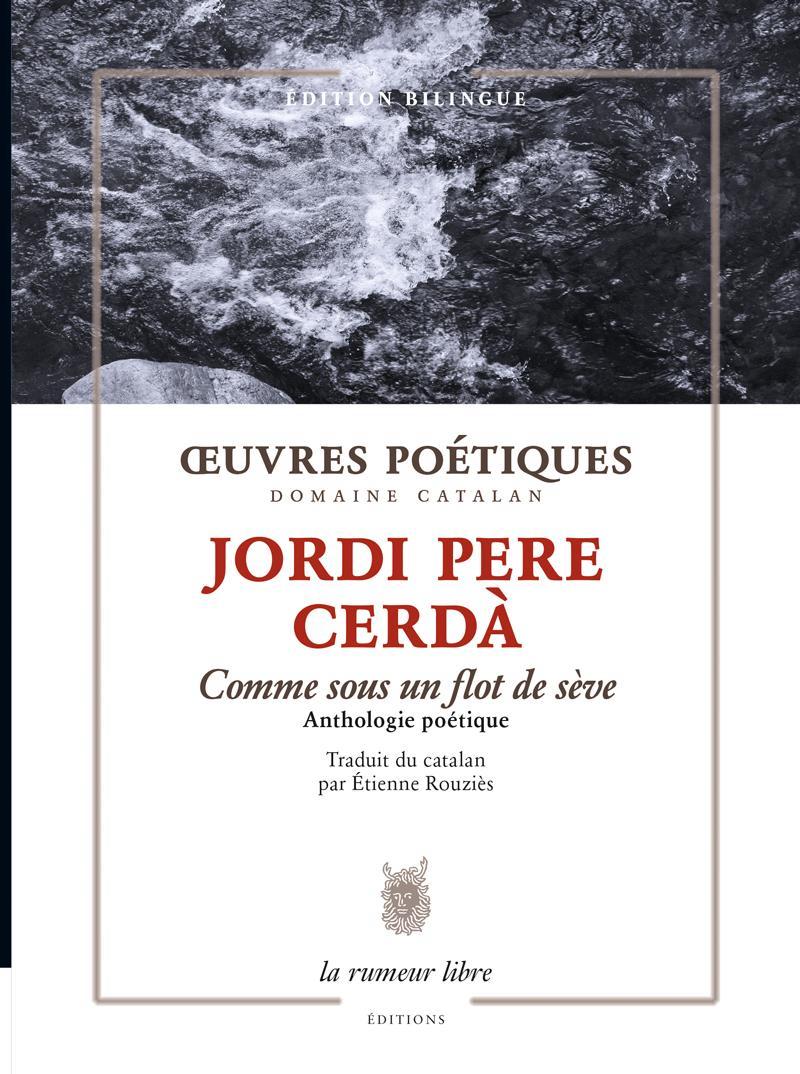

Today, his legacy is preserved at the Library of Catalonia and is slowly being translated into French. The most recent translation is Comme sous un flot de sève, a poetry anthology translated by Etienne Rouziès (La rumeur libre, 2020). Apart from the 2013 edition of the book Obra Poètica (Poetic Work, Viena), most of his oeuvre is out of print.